Platinum Group Metals – Automotive Recycling Supply

Platinum Group Metals – Automotive Recycling Supply

By World Platinum Investment Council - WPIC®

16 Oct 2025

The opinions expressed in this report are those of World Platinum Investment Council (WPIC) and are considered market commentary. They are not intended to act as investment recommendations. Full disclaimers are available at the end of this report.

Executive summary

Recycling forms a core component of platinum group metals (PGM) supply, having, for example, accounted for an average of 24% of total platinum supply over the five years to 2024. PGMs retain their functional properties after recycling, which means that recycled metal is interchangeable with mined metal in end-use applications, allowing PGMs to play an important role in the circular economy and sustainable design practices. Moreover, the recyclability of PGMs is becoming increasingly key to overall platinum supply, as developed economic mine reserves deplete; primary supply has declined at a -0.7% CAGR since 2015.

Total recycling supply consists of automotive recycling supply from the recovery of PGMs contained within the autocatalysts in end-of-life vehicles (ELVs), jewelry recycling and open loop industrial recycling, primarily from electronics (separately, there is significant closed loop industrial recycling that is not captured in published recycling volumes). Automotive recycling makes up three-quarters to 84% of total, published PGM recycling supply, depending upon the metal, with palladium the dominant metal when it comes to the economics of automotive recycling.

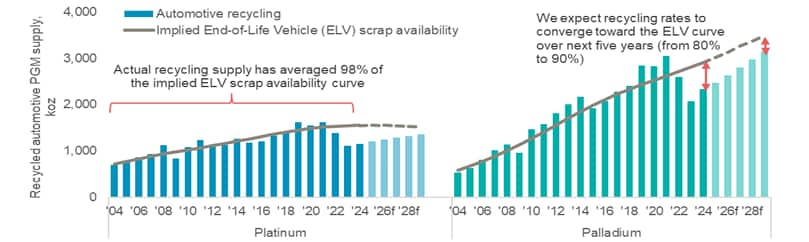

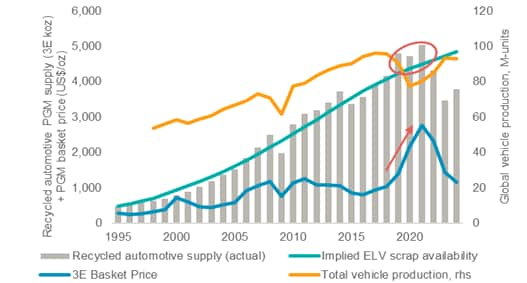

WPIC research has identified that automotive PGM recycling supply is more price elastic than traditionally believed. This helps to explain why platinum recycling supply was depressed between 2022 and 2024, when the low PGM basket price led to some hoarding of spent autocatalysts by scrapyards that lacked the economic incentive to sell recovered catalysts. Higher PGM prices in 2025 are supportive of recycled supply growth (Figure 1). However, platinum automotive recycling supply is not expected to recover to the peak level reported in 2021, and we expect this to contribute to sustained platinum market deficits through 2029.

Figure 1: PGM automotive recycling supply is forecast to trend higher, but platinum will not return to its 2021 peak

Background

California introduced vehicle emissions legislation in 1966 to combat rising smog, leading to the 1970s development of catalytic convertors, or autocatalyst, for vehicles to meet emissions legislation. The majority of automotive emissions control technologies are based on PGMs – primarily platinum, palladium and rhodium – due to their catalytic properties, which enable reductions in harmful pollutants such as carbon monoxide (CO), nitrous oxide (NOx) and unburnt hydrocarbons (HC).

Automotive demand for platinum is underpinned by two factors: annual vehicle production and autocatalyst loadings. With the first autocatalysts fitted to cars in the 1970s, significant quantities of ‘in-use’ PGMs have accumulated and are theoretically able to support future supply requirements, when vehicles reach the end of their economically useful lives and are scrapped. Globally, legislation promotes recycling and the PGM industry has a mature recycling supply chain.

However, in practice, PGM recycling volumes are a function of both the availability of spent autocatalysts and the economic incentive to recycle autocatalysts. Notably, the significance of the economic incentive to recycle autocatalysts can be overlooked, in part because the value chain for PGM automotive recycling is opaque. Market participants may assume recycled PGM supply is completely price agnostic because refiners of scrap material generate stable margins through price cycles. This simplified assessment of recycling supply ignores the different gearing to PGM prices faced by scrapyards and aggregators that can impact on recycled supply volumes.

Recycling spent autocatalysts

Recoveries of PGMs from spent autocatalysts are well over 95% when using the correct process such as pyro and/or hydrometallurgical methods. However, before recyclers can get access to used autocatalysts, vehicles need to reach the scrap yard. A vehicle reaches its end-of-life when the economic cost of maintaining or restoring its roadworthiness is higher than outright replacement.

In general, as a vehicle is used and ages, the accumulation of wear and tear increases the maintenance requirements, which in turn increase the likelihood of it being scrapped. A vehicle has the highest chance of getting scrapped between 10 and 20 years of use from new, with around half of all vehicles being scrapped within that period. Newer vehicles may also be deemed end-of-life if they have been in a serious accident.

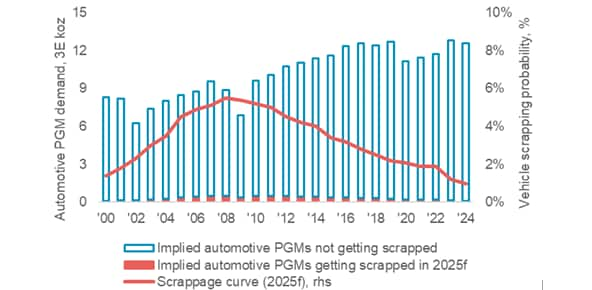

With decades worth of historical data, market participants have developed scrappage curves that assign a probability to the likelihood of a vehicle being scrapped in each year of its life. Since a scrappage curve estimates a distribution of the various model years of vehicles likely to be scrapped, it is possible to reconcile that data with the applicable emissions legislation that the scrapped vehicles were subject to, and therefore the likely PGM loadings in those vehicles’ autocatalysts. Accordingly, a scrappage curve functionally also helps to calculate a theoretical availability of recycled automotive PGM supply (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Implied availability of recycled automotive PGMs supply in 2025 derived from the estimated production years of vehicles being scrapped.

It is worth noting that not all the theoretically available PGMs (determined from a scrappage curve) enter the recycling value chain. Forecasts for recycled automotive PGM supply need to be adjusted downwards by 40%-45% to reflect real world considerations, including:

- Loss in use (LIU): Over the operating life of an autocatalyst, physical wear and tear can lead to minor losses of PGM-containing substrate.

- Exports: The automotive industry is underpinned by global trade. Trade is most associated with new parts and vehicles. However, there is also a significant trade in second-hand vehicles, typically from developed markets to emerging markets where new vehicles are often less affordable. Regions such as Africa or South America, which import second-hand vehicles, often lack the necessary recycling infrastructure to recover PGMs at scale.

- Catalyst attachment: Some end-of-life vehicles do not have an autocatalyst or the catalyst was inadvertently sent to landfill.

- Recovery losses: There are low single-digit PGM losses incurred when de-canning, smelting and refining spent autocatalysts.

- Other scrap inclusions: Aftermarket parts for maintenance and repairs (as well as to replace stolen catalytic converters) over a vehicle’s useful life is additive to catalyst volumes and total recoveries.

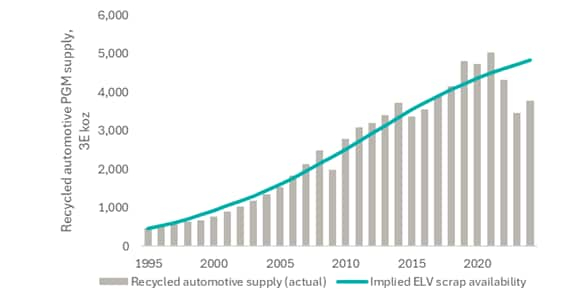

Back-checking the modelling of implied ELV scrap availability against actual automotive recycled PGM supply since 1995 indicates that actual supply has been 98% of forecast ELV scrap availability (Figure 3), demonstrating a strong alignment.

Figure 3: Historical recycled automotive PGM supply (as reported) is around 98% of recycled automotive PGM supply estimated using an ELV scrappage curve adjusted for loss factors

Deviations from the scrappage curve

While over the last 30 years recycled automotive PGM supply has, in general, aligned quite well with implied scrap availability from an ELV curve, deviations can occur. This happens when there are ‘shocks’ that impact the physical supply of spent autocatalysts or the economic incentives to recycle.

Physical supply shocks

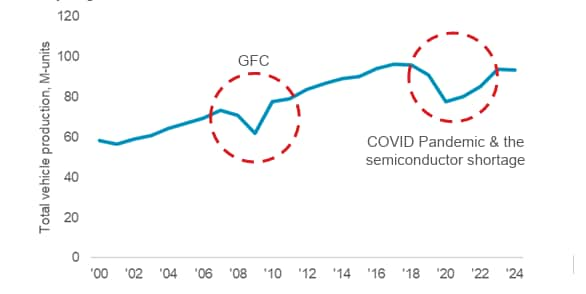

Vehicle scrapping, used car markets and new car markets are not strictly independent, and two such instances in recent history where the interplay between these markets impacted PGM recycling were during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC, 2008/9) and the COVID-19 pandemic (2020~2022). During the GFC and at the height of the pandemic, new vehicle demand collapsed (Figure 4) with economic uncertainty leading to consumer caution over large expenses such as new vehicles.

Figure 4: Shocks to new vehicle markets can impact the pipeline of used car recycling

Furthermore, during the pandemic, lockdowns and subsequent work-from-home trends reduced annual mileage and deferred vehicle depreciation. The result of economic caution and less driving was that consumers held on to their current vehicles for longer, which in turn reduced the supply of used vehicles for recycling. In addition, automakers over-estimated the downturn in demand for new vehicles as a result of the pandemic, cutting their orders of semiconductors, which were then diverted into other sectors (predominantly consumer electronics). When they tried to respond to higher-than-expected demand they found themselves unable to procure sufficient semiconductors, which further constrained new vehicle production and added to deferred consumer scrappage decisions. Reflecting the shortage of new vehicles, used vehicle prices increased by as much as 50%.

Economic incentives

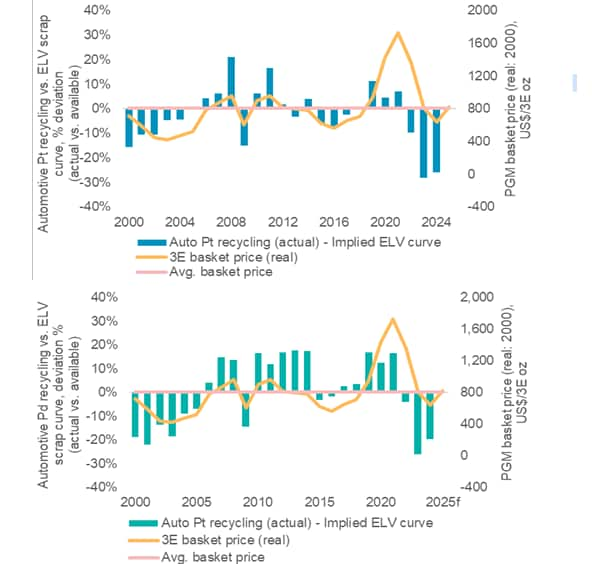

A scrappage curve can help forecast how many spent autocatalysts will enter scrapyards in a given year. However, scrappage curves do not demonstrate whether it is economically attractive to actually recycle those autocatalysts. Based on prevailing markets, automotive PGM recycling may increase with higher PGM prices or decrease with lower PGM prices. Notably, in 2019, 2020 and 2021, recycled automotive PGM supply exceeded estimates from the ELV scrappage curve by an average of 10%. It appears that sharply higher palladium and rhodium prices (Figure 5) offered a greater economic incentive to increase recycling rates, despite the COVID-19 pandemic weighing on the physical supply of used vehicles for scrapping. Conversely, as the prices of palladium and rhodium began receding from 2022, recycled automotive PGM supply undershot estimates from the ELV scrappage curve by an average of 18% between 2022 and 2024.

Figure 5: Elevated Pd and Rh prices 2019-2021 supported a record basket price (3E*) offering the economic incentive to boost automotive recycling

Plotting actual platinum and palladium recycled automotive supply against the 3E basket price (platinum, palladium and rhodium) further reinforces scrap’s supply elasticity to prices (Figure 6). In general, where real basket prices are below their historic average price, recycled automotive PGM supply underperforms expectations from the implied ELV scrap curve.

Figure 6: Excess/depressed automotive recycling volumes (vs. implied ELV curve) occur during periods of elevated/below average PGM prices

Price elasticity and the automotive recycling supply value chain

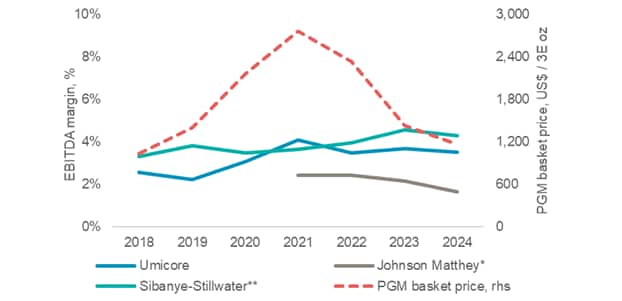

To explain why PGM prices are the key driver underpinning recycled automotive PGM recycling supply requires an understanding of its value chain. Downstream, the business model for a refiner of secondary PGMs is to achieve a spread between the price paid for spent autocatalyst feedstock and the price achieved for selling refined PGMs (typically market prices). These are low margin businesses, with the spread covering the largely controllable and known costs of smelting and refining recycling feedstock. Refiners use hedging to avoid price risks and are therefore able to lock-in stable margins through PGM price cycles (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Smelting and refining recycled PGMs generates broadly stable margins through price cycles

Analysis shows that the price paid by a refiner to an upstream aggregator equates to between 90% or 95% of the value of the PGMs contained within an autocatalyst. The common misconception that PGM recycling is price agnostic arguably arises at this juncture in the value chain.

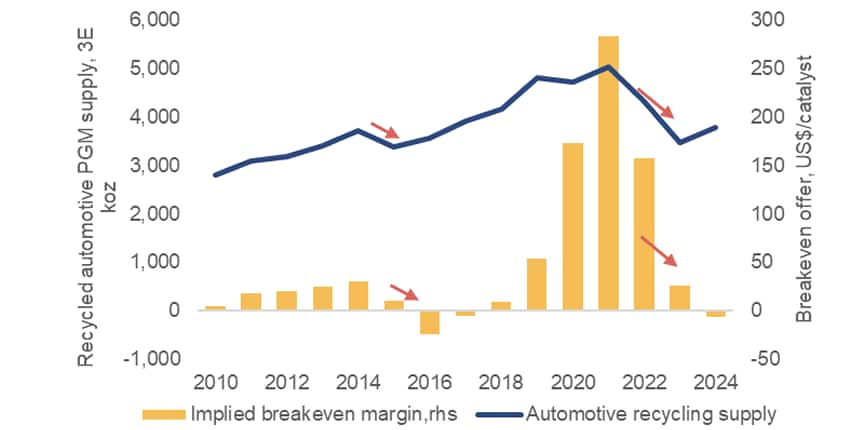

There is a lack of reported financial data from the fragmented scrap aggregation industry. Unlike PGM refiners, scrap aggregators’ processing and overhead costs are not a nominal proportion of their total costs. The costs an aggregator incurs to prepare autocatalyst feedstock for PGM recycling are largely fixed. These costs are in addition to the costs of purchasing spent autocatalysts from scrapyards, which are variable. The theoretical break-even price for an aggregator is the highest price an aggregator could offer a scrapyard for a spent autocatalyst before its total costs exceed the revenue it would receive from a PGM refiner for the feedstock. Given that other costs are largely fixed, to turn a profit, the price offered by an aggregator to a scrapyard would need to be lower than its break-even price.

Figure 8: Scrapyards will hoard spent autocatalysts when offer prices are low, which in turn leads to depressed automotive PGM recycling supply

Analysis demonstrates that there was a sharp reduction in offer prices from aggregators to scrapyards between 2021 and 2024, which could explain anecdotal evidence that scrapyards were hoarding spent autocatalysts in expectation of higher future prices. This led to falling platinum automotive recycling supply during that time. Notably, scrapyards can hoard autocatalysts because they recognize multiple revenue streams from recycling vehicles with everything from steel, fabrics and used engine oil getting recycled when a vehicle is scrapped.

Outlook for PGM automotive recycling supply

Recycled automotive PGM supply is price elastic and low PGM prices from 2022 to 2024 disincentivized recycling supply. Recent PGM price increases have improved recycling economics and the downward trend that platinum automotive recycling supply has exhibited since 2022 is forecast to reverse in 2025, when it is expected to grow 6% to 1,210 koz.

Looking out to 2029 (Figure 8), WPIC expects automotive recycling supply to increase by 4.7% CAGR and 7.5% CAGR from 2024 to 2029 for platinum and palladium, respectively. This is underpinned by the increasing availability of spent autocatalyst supply and the year-to-date rise in the basket price. However, since automotive PGM recycling supply is price elastic, growth in platinum recycling supply could be capped by the transition of palladium markets into surplus from 2027, palladium being the dominant metal in recycling economics. Palladium market surpluses could mean that potentially lower palladium prices may limit the economic rationale to increase automotive recycling supply.

Accordingly, we expect platinum automotive recycling supply to recover to only 95% of the available supply implied by end-of-life vehicle (ELV) scrappage curves (vs. 80% from 2022 to 2024 and 110% from 2019 to 2021). The reduction in forecast platinum automotive recycling supply relative to historic levels is a contributory factor in the platinum deficits that WPIC anticipates will occur through 2029.

It is also worth noting that, with automotive platinum demand peaking in 2007, many of the vehicles from that period would, by now, have already entered scrapyards. The historic peak in platinum automotive demand has led to platinum’s implied ELV availability curve to crest in 2025. Accordingly, despite our expectations for some recovery in supply, the future trajectory of the ELV availability is on a downward path and we therefore believe that recycled automotive platinum supply peaked in 2021.

Figure 9: Overview of platinum and palladium recycling supply versus supply/demand balances

| koz | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025f | 2026f | 2027f | 2028f | 2029f |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Platinum Automotive recycling supply | 1,619 | 1,370 | 1,114 | 1,143 | 1,210 | 1,274 | 1,332 | 1,384 | 1,437 |

| YoY change in recycling supply | +65 | -249 | -256 | +29 | +67 | +64 | +58 | +52 | +53 |

| Supply/dem and balance | 1,491 | 1,066 | -712 | -968 | -850 | -591 | -580 | -590 | -486 |

| Palladium Automotive recycling supply | 3048 | 2,062 | 2,071 | 2,329 | 2,508 | 2,701 | 2,911 | 3,122 | 3,336 |

| YoY change in recycling supply | +212 | -446 | -531 | +258 | +179 | +193 | +210 | +211 | +214 |

| Supply/dem and balance | 518 | -17 | -1,164 | -689 | -260 | -83 | 106 | 125 | 426 |

Source: Metals Focus 2022 to 2025 (platinum) and 2022 to 2024 (palladium), Company guidance, WPIC research

Read the full article at: Platinum Group Metals – Automotive Recycling Supply - CME Group